Hunting is about getting as close to your game as possible but close can be a relative term. In my 45-plus years of hunting on six different continents, I’ve gained enough experience to know that getting up close and personal isn’t always an option, especially in the mountains or the more open plains. For this reason, I’ve spent considerable time equipping myself and practicing for those eventual long-range scenarios. I’m well practiced out to 800 yards and have taken several animals at or near that range. There’s no magic to it. It just takes the right gear and dedication. Despite advice on the internet, getting closer isn’t always an option. Here are 10 rules I live by while long-range hunting.

1. Know Your Range

Over the years there have been some innovative means of estimating range from MOA reticles to focus-style rangefinders. A few decades ago, it was all we had, but none of them were 100 percent accurate and most less than 75 percent. These days, any serious long-range shooter owns a laser rangefinder. These are available in stand alone units, but I much prefer to have a combination binocular/rangefinder for hunting, as it one less item I have to carry. The lasers in the high-quality units are accurate to one yard at 600 yards and when shooting at long range, this type of accuracy is a must. Most rangefinders are rated on highly reflective surfaces like mirrors, and their actual range-finding ability of a deer-sized animal is likely 50-60% of their rating. If you plan on shooting out to 1,000 yards, then get a rangefinder rated for 2,000 yards.

For hunting, a rangefinder that calculates angle and true ballistic distance is a must as well. Whether shooting uphill or downhill, your true ballistic distance will be shorter than the actual range. With closer range shots, angle plays little role, but at longer ranges it can make a big difference, especially when shooting at steep angles. In the mountains for example, it’s not uncommon for the true ballistic distance to be 50-100 yards difference from actual range at ranges from 500 plus yards. This can have a significant effect on you point of impact if not compensated properly for. When I took my desert ram in Mexico, the true distance was 618 yards but the compensated ballistic distance was 586 yards. It was a steep uphill shot.

2. Select the Right Cartridge

I’m not a fan of extreme-velocity cartridges for long-range hunting and typically, something that leaves the muzzle at around 3,000 feet per second with a fairly heavy for calibre bullet is ideal. If you take a look at most of the extreme-range chamberings like the 50 BMG, 408 Chey Tac, and 338 Lapua, they are all in that muzzle velocity range. It seems this is where bullets stabilize well, accuracy is good and velocity is still sufficient for bullets to expand at longer ranges. I also prefer lower recoil chamberings as most long-range shooting is done from the prone position, so my choices are in the 6.5mm to .30 calibre range. Cartridges like the new 7 PRC, 6.5 PRC, and 300 Winchester Magnum are all favourites with long range hunters, but there are another couple dozen that fit the criteria. I’m far from a cartridge snob and just want one that fits the criteria of a muzzle velocity around 3,000 feet per second and that it’s capable of delivering a heavy for calibre bullet at over 1,600 feet per second at the maximum ranges you intend on shooting.

3. Select the Right Rifle

Obviously, accuracy is paramount and the further you want to shoot, the more accurate the rifle must be. For those never intending to shoot in excess of 500 yards, a rifle capable of MOA accuracy would be your minimum. If you plan on shooting beyond that range, then accuracy must increase proportionally. For example, a 1,000-yard rifle would need to be capable of .5 MOA accuracy. I wouldn’t considering anything but a bolt-action rifle for long-range hunting, as it’s the platform that offers the best accuracy with the option of a quick follow up shot.

There are lots of schools of thought as to whether barrel length and rifle weight effect accuracy. They don’t. But rifle fit and comfort certainly do. It’s been my experience that few people shoot extremely light-weight rifles well and there’s no question that heavier rifles are more stable. With that said, I’ve got a couple sub six-pound rifles that shoot .38-.5 MOA easily, but they fit me like a glove. Barrel length, within reason, plays no role in accuracy and with many cartridges, the velocity loss per inch is minimal as well. If I were looking for a super light-weight mountain rifle, I wouldn’t hesitate to shoot a rifle with a 20-22-inch barrel. For something I wasn’t packing around in the mountains, a longer barrel may offer better balance and the added weight does help with stability. Also, you want a barrel with a faster rifling twist rate, so it stabilizes the longer bullets associated with long-range shooting better.

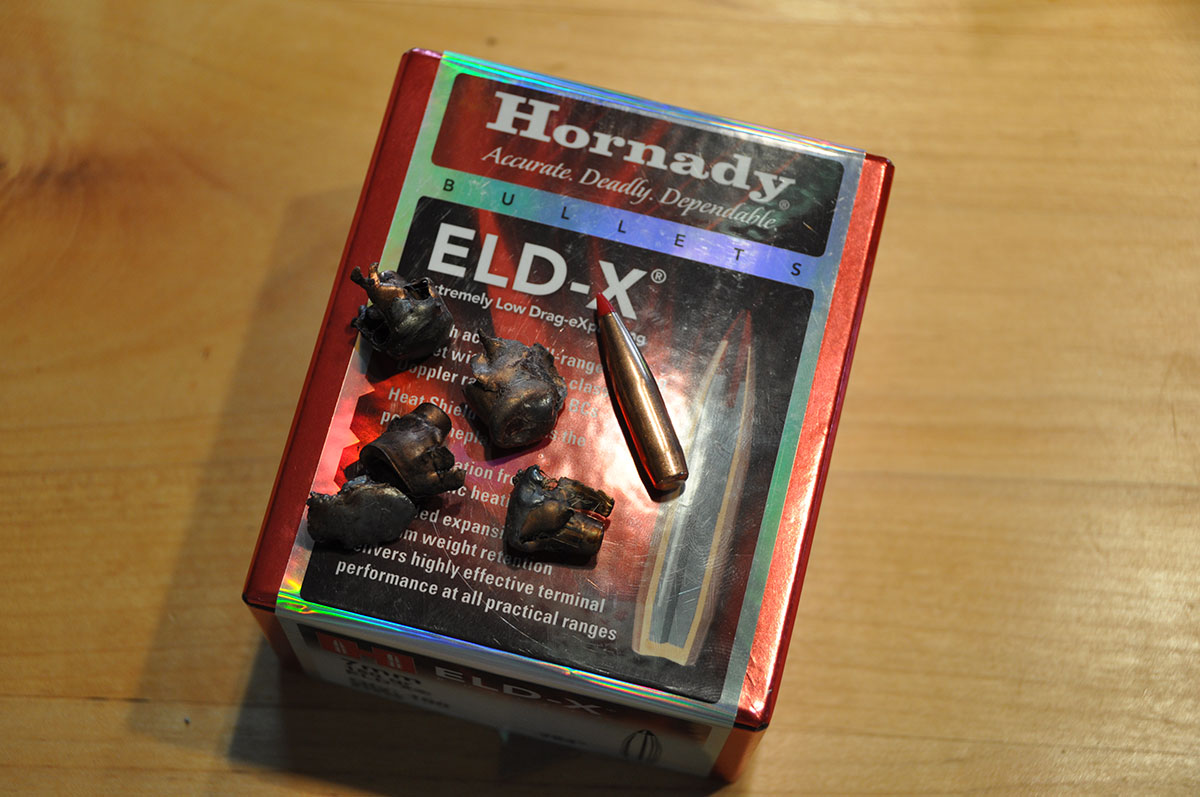

4. Select the Right Bullet

With the proliferation of long-range hunting bullets hitting the market these days, the choices have never been greater. The perfect long-range hunting bullet must obviously be accurate in your rifle, be heavy for calibre, have a high ballistic co-efficient and expand reliably down to impact velocities of 1,600 feet per second. While there are lots of great hunting bullets out there, long-range bullets are specialized. They are typically of cup and core construction. This construction method offers the most consistent accuracy for expanding hunting bullets and it allows bullets to expand at lower impact velocities than say bonded or mono metal bullets.

There was a time that loads for long-range hunting were strictly the domain of handloaders, but factory ammunition is becoming markedly better and now it’s possible to get maximum accuracy from a rifle using factory ammunition. If I can offer one word of advice, it’s to check accuracy at the ranges you intend shooting. While bullets may shoot impressive groups at 100 yards, groups often open up at longer ranges due to the bullet destabilizing the longer it is in flight. I’ve seen some traditional hunting bullets that shoot under MOA at 100 yards, open up to two MOA at 500 yards.

5. Select the Right Optics

While the argument about long-range optics usually begins with first or second focal plane, I’m going to say right now that it really doesn’t matter for hunting optics. I shoot all second focal plane scopes. What does matter is that the scope has a reliable means of ballistic compensation that allows you to maintain the same point of aim (POA) and same point of impact (POI) through a wide variety of ranges. Simply put, I want to put the crosshairs exactly where I want the bullet to hit regardless of the range. This is easily accomplished with a ballistic-type reticle with multiple hashmarks or with exposed turrets that are turned for the range being shot. I use both systems, and each has its advantages. The turrets allow for longer ranges and with the addition of custom-burned yardage turrets, it’s just a simple matter of turning the turret to the desired yardage rather than having to count clicks as with MOA markings on your turret. The ballistic reticles typically max out around 800 yards and they are not usually yardage indicated, so you need to remember what yardage each hashmark represents. They are quicker to use, however, as there is nothing to adjust. I’d say pick a system you like best and become intimately familiar with it. They both work.

I also like a scope that has a maximum magnification of 15 power or greater. More magnification means a more accurate point of aim but it’s also important to have a scope with a lower end magnification for those closer shots. My go to scope is a 3-18×50. Long range scopes will have at least a 30mm tube. The larger tube allows for more MOA adjustment. Traditional one-inch tubes typically don’t allow enough adjustment to shoot past 500-600 yards if you are relying on turning turrets for elevation compensation.

6. Take a Rest

Most long-range shots, taken under hunting conditions, are from the prone position. It is the steadiest position to shoot from, so most of my rifles are equipped with a bipod. The bipod does add forward weight and throw a rifle off balance while shooting from other positions, however, so I prefer a bipod that is easily detachable. This way, if I’m hunting somewhere that a quick long-range shot may be required, I can leave the bipod attached. If the chances of an off-hand shot are greater and I’ll have time to set up for a long-range shot, then I will carry the bipod in my backpack. While supporting the front of the rifle is critical, so too is supporting the rear on longer-range shots. Rather than carrying an additional aid for this, I typically just remove my sweater or jacket and roll it up to support the rear. This ensures your rifle is rock steady with the minimum amount of gear.

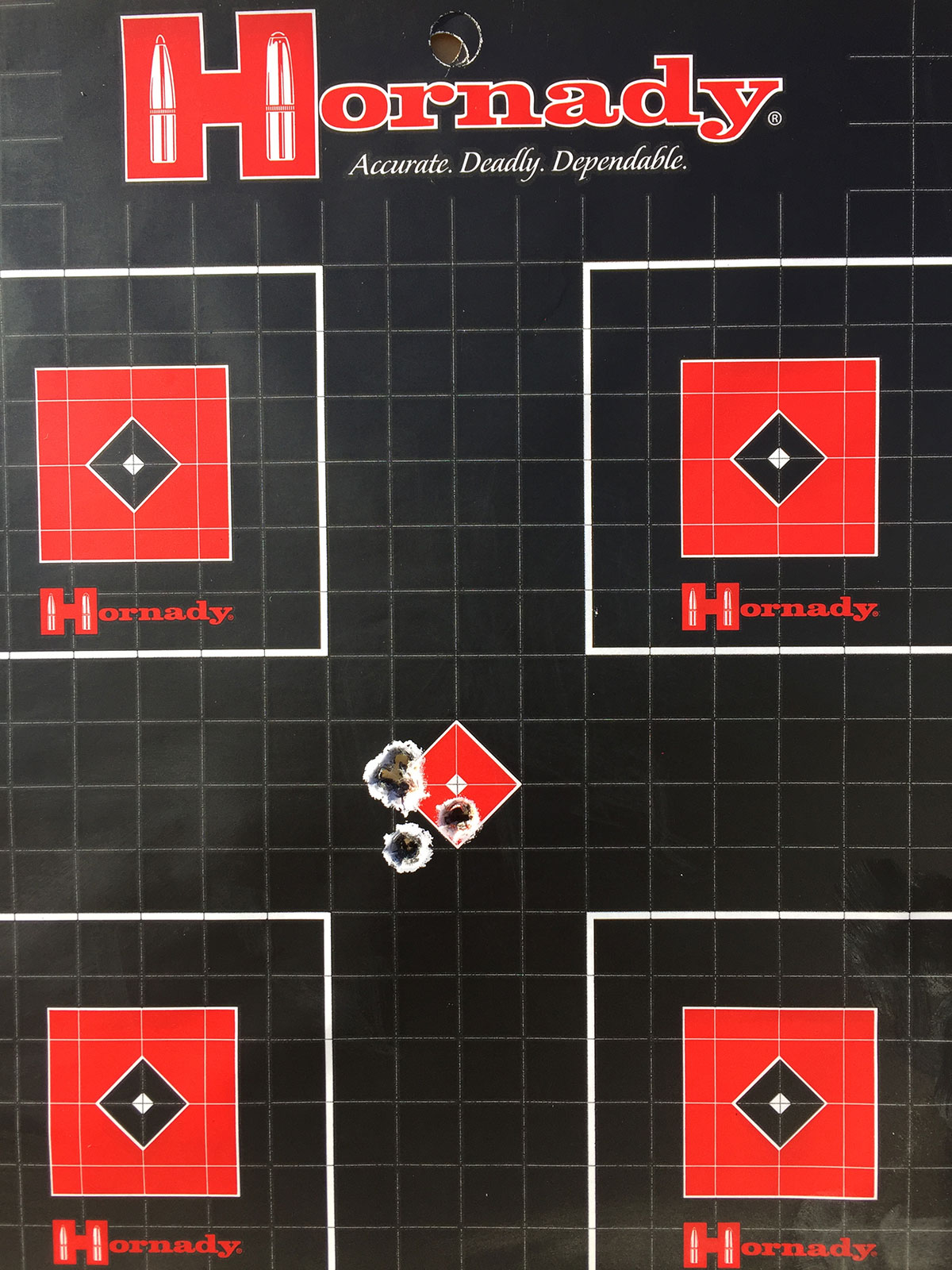

7. Center Mass Matters

If you aren’t willing to practice at the ranges you plan on shooting, under actual field conditions, you should not be taking long range shots, period. Once your rifle is sighted in, get off the bench. It’s time to start practicing under the conditions and from the positions you’ll be shooting from when hunting. I’m a big fan of shooting steel at longer ranges, as the sound of a bullet banging a gong is the real reward when practicing. Forget about shooting tight groups and concentrate on aiming for centre mass on the gong. Long-range hunting isn’t the same precision game that long-range target shooting is. There are no precise aim points nor opportunities to shoot tight groups. With long-range hunting you get one shot and as long as you put it somewhere close to center on that 10-inch circle where the vitals reside, you’ve done your job. Some of the best F-Class shooters I know are the worst long-range hunters, because they can’t make that transition to shooting for centre mass in the vitals. It takes practice! Obviously, all the basics of breathing and trigger control apply, but the real practice is coming to terms with not aiming at a tiny dot but rather center mass.

8. Learn to Read the Wind

The wind is the greatest variable and the least controllable for long-range shooting. There are instruments to measure wind velocity and they can be a great aid but often, the wind where the shooter is can be vastly different than at the target. An effective long-range hunter needs to be able to read these variables by paying attention to the environment around you. Take notice of how the grass or trees are blowing at your location versus at the target. Wind is easy to compensate for when you know the exact wind speed but when you don’t, there’s no substitute for experience and that only comes from practicing in the field. The best method I’ve found is to measure the wind at your location with a wind meter and then compare the environmental signs near the target. If the grass is bending over twice as much at the target, then compensate more than what the wind meter says at your location.

9. Keep Your Head Down

Shooting form is critical and the worst habit I see is lifting one’s head immediately after the shot. There is no better view of how the animal reacted after a shot than through your scope, yet I constantly see people searching with their naked eye. Evaluating where the animal is hit is critical in determining if a rapid second shot is required and how you may need to adjust your elevation or windage. Keeping you head down will also improve your accuracy. Learn to keep your head down and to work the bolt while looking through the scope.

10. Know When to Say No

The absolute most critical skill a long-range hunter can learn, is when to say no and walk away from a shot. There is an entire new set of ethics that come with long-range hunting versus shooting at targets and if you are not 100-percent certain of making the shot, then the only option is to try to get closer or simply walk away. If you are not willing to do this, you shouldn’t be taking long-range shots at animals.

Top Five Long-Range Hunting Rifles under $2,000

- Sako S20

- Seekins Havak Pro Hunter 2

- Bergara HMR Carbon Wilderness

- Winchester Renegade Long Range

- Tikka T3x Ultimate Precision Rifle (UPR)

Top Five Mistakes hunters make shooting long range.

- Not using a rear rest

- Lifting their head after the shot

- Rushing the shot

- Not getting an accurate range to target

- Not practicing enough

Checklist for taking a long-range shot

- Know your range

- Wait until the animal is calm and not moving

- Take a solid rest

- Control your breathing

- Aim at center of vitals

- Squeeze trigger

- Keep your head down

Per our affiliate disclosure, we may earn revenue from the products available on this page. To learn more about how we test gear, click here.